Building students' literacy in Science

Felicity also presented a professional learning session on building literacy skills in the Science classroom earlier this year. The recording of that session is available here (and the accompanying teacher activity pack here).

What is science literacy?

There are two key terms to unpack when discussing literacy in a science classroom:

- Literacy in science

- Scientific literacy

1. Literacy in science refers to the ability to read, write, and communicate science.11 In the Australian science classroom, student literacy is dependent on

- English language knowledge and skills

- Scientific language knowledge and skills.

This means that a student who is finding it difficult to engage with the ideas of science may be needing support to decipher the languages (words and texts) used.

2. Scientific literacy is the ability to engage with scientific knowledge and evidence, to apply it to real-world problems and then make informed decisions.1 It involves critical thinking, reasoning, and evaluating. Scientific literacy rests on a foundation of literacy in science as application requires knowledge and skills.

There is a clear evidence-based link between literacy and scientific engagement and achievement, including how

- students with higher levels of literacy achieve higher scores in science-based assessments9, 10, 13, 15

- students with better literacy are more likely to continue studying science after secondary school4

- higher literacy levels allow individuals to engage with the moral, social, and ethical implications of science, and consider its role in daily life.2, 8, 14

Literacy is essential to engage with, understand, evaluate, and communicate scientific ideas. That means integrating literacy instruction into science classrooms is a key component of how we, as science teachers, can support student outcomes.7, 12, 16

Activities to support literacy in science

Integrating explicit, consistent literacy instruction is essential in supporting science students3, 5, 6 and it doesn’t have to be hard for teachers.

The following are examples of activities I’ve used and have seen work in the Science classroom. They can be easily adapted to many class contexts, you may have come across some of these, or their variations, before. The activities are categorised into:

- Understanding words

- Understanding questions

- Understanding texts

They can be readily modified to support differentiation: targeting the students in your class with the key skills of reading, writing, speaking, questioning, and explaining.

Understanding words

1. Don’t say that

- Give one student a key term and a list of associated words they cannot use to describe it.

- This student gives the others clues as to what the term is, without using the forbidden words.

- The student who correctly identifies the key term takes the next turn, with a new word (and forbidden list).

2. Morphemes: growing words

- Display words with the same base (root) but different prefixes (start) and/or suffixes (end).

- Lead students through a discussion to identify the meaning of the base word, prefix, and suffix options.

- Students use these to create as many words as they can by combining the options in different ways.

- Discuss the combinations that form true and unreal words, and their possible meanings.

- Highlight any key terms that have been found.

3. What’s that mean?

- Have students draw a table in their books, with column headings of ‘Word’, ‘Everyday meaning’, and ‘Scientific meaning’.

- Fill in the table to show the difference between the technical scientific definition, and the everyday usage of the term.

- Where there are multiple scientific meanings, label the different meanings with the disciplines they come from.

Understanding questions

1. Performing Science

- Students work in small groups to develop a non-written response to a prompt, such as a question or key term needing a definition.

- Ask students to identify and tailor their response to a specific audience and context. E.g. preschool science television show, street mime for the general public, drawing for an information poster.

2. Poorly explain…

1. Ask students to respond to a question in a way that is technically correct, but choose at least one way to do so poorly. For example, answering the question in a way that is

- confusing

- misleading

- vague

2. Have students share their answers with a partner who guesses what the possible question could have been.

3. Then create a proper/clearer answer and identify the improvements it makes over the original answer.

3. Question starters

- Prepare a set of prompt sheets such as the example provided. These could be literal, inferential, or evaluative levels of questioning.

- Read through a prompt text. This could be anything from a practical results table, a chunk of theory, or a Science as a Human Endeavour article.

- Divide students into pairs or small groups.

- Students create a list of questions relevant to the text.

Understanding texts

1. Headings, please

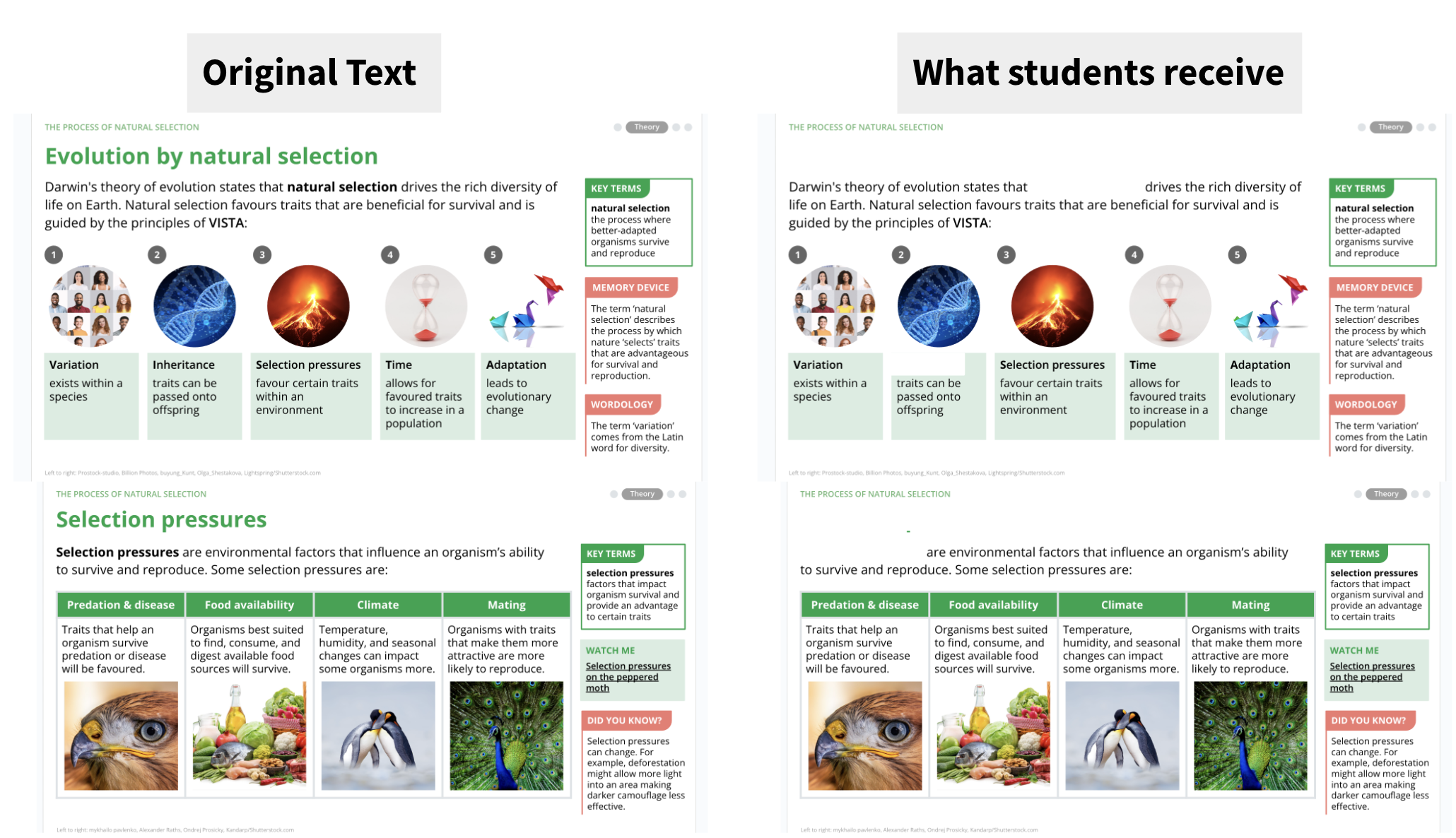

- Choose an unseen text, such as some Edrolo lesson slides or scientific report.

- Blank out all headings and subheadings.

- Make a copy for each student.

- Ask students to read through the text and write in the (sub)headings they think are missing.

- Ask students to highlight the section(s) of text that prompted their choice of (sub)heading.

2. Human interest story

- Provide students with a text that focuses on the Science as a Human Endeavour aspect of a new topic.

- Ask students to highlight the section(s) of text that give them clues as to what the topic may be about.

- Have students create a summary of the topic, including

- what they think it is about

- what they already know

- key words they want/need to understand

- the impact that understanding this topic could have

- anything they find interesting or want to learn more about

3. 'Unjumble' my text

- Choose a text not previously seen by students, such as a textbook page or scientific report.

- Cut each section and put them out of order.

- Create a class set of the jumbled sections.

- Have students read through the sections.

- Ask them to rearrange the pieces into a coherent page of text.

- Compare their answers to the original layout and use this to prompt discussion around navigation of texts and the flow of ideas.

References

1 Australian Academy of Science. (2015). Science literacy: What it is, how to assess it, and why it matters. Retrieved from https://www.science.org.au/learning/general-audience/science-literacy-what-it-how-assess-it-and-why-it-matters.

2 Australian Academy of Science. (2019). Science and the Australian Public 2019. Retrieved from https://www.science.org.au/supporting-science/science-and-the-australian-public-2019

3 Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). (2016). Literacy and numeracy in science: Exploring the intersection of disciplinary knowledge, literacy and numeracy. Retrieved from https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=research_conference

4 Australian Council for Educational Research. (2019). Science literacy and achievement in Australia. ACER. https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=ozpisa

5 Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2014). Literacy and numeracy in science. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/resources/curriculum-connections/portfolios/literacy-and-numeracy-in-science/

6 Australian Science Teachers Association (ASTA). (2015). Science literacy: Position statement. Retrieved from https://asta.edu.au/advocacy/position-statements/science-literacy-position-statement

7 Gardner, P., & Grace, M. (2010). Science literacy: Preparing Australian students for the 21st century. Teaching Science: The Journal of the Australian Science Teachers Association, 56(1), 45-50. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756809990335

8 Gregory, J. (2014). Scientific literacy and the moral imagination. Science & Education, 23(10), 2157-2172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-014-9682-2

9 Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. (2006). The Four-Phase Model of Interest Development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

10 Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., Kelly, D. L., & Fishbein, B. (2020). TIMSS 2019 International Results in Mathematics and Science. Retrieved from Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center website: https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/international-results/

11 National Research Council. (2012). A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. The National Academies Press https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/13165/a-framework-for-k-12-science-education-practices-crosscutting-concepts

12 National Science Teachers Association. (2016). NSTA Position Statement: Science and Literacy. https://www.nsta.org/nstas-official-positions/science-and-literacy

13 Purcell-Gates, V., Duke, N., & Martineau, J. (2007). Learning to read and write genre-specific text: Roles of authentic experience and explicit teaching. Reading Research Quarterly, 42(1), 8–45. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.42.1.1

14 Rennie, L. J., Goodrum, D., & Druhan, A. (2021). Science literacy and the moral, social and ethical implications of science: A cross-curriculum priority? Curriculum Perspectives, 41(2), 189-200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-021-00139-x

15 Shaffer, J. F., Ferguson, J., & Denaro, K. (2019). Use of the Test of Scientific Literacy Skills Reveals That Fundamental Literacy Is an Important Contributor to Scientific Literacy. CBE life sciences education, 18(3), ar31. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-12-0238.

16 Shanahan, T., & Shanahan,C. (2008). Teaching Disciplinary Literacy to Adolescents: Rethinking Content Area Literacy. Harvard Educational Review. 78. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.78.1.v62444321p602101